In response to the UK government's AI strategy, Ofgem published ethical AI guidance in May 2025, intended to give utility companies direction on how to implement AI while protecting customers. The intention is laudable. We'd all agree that customers need to be treated fairly, decisions should be clear, and vulnerable customers must be supported.

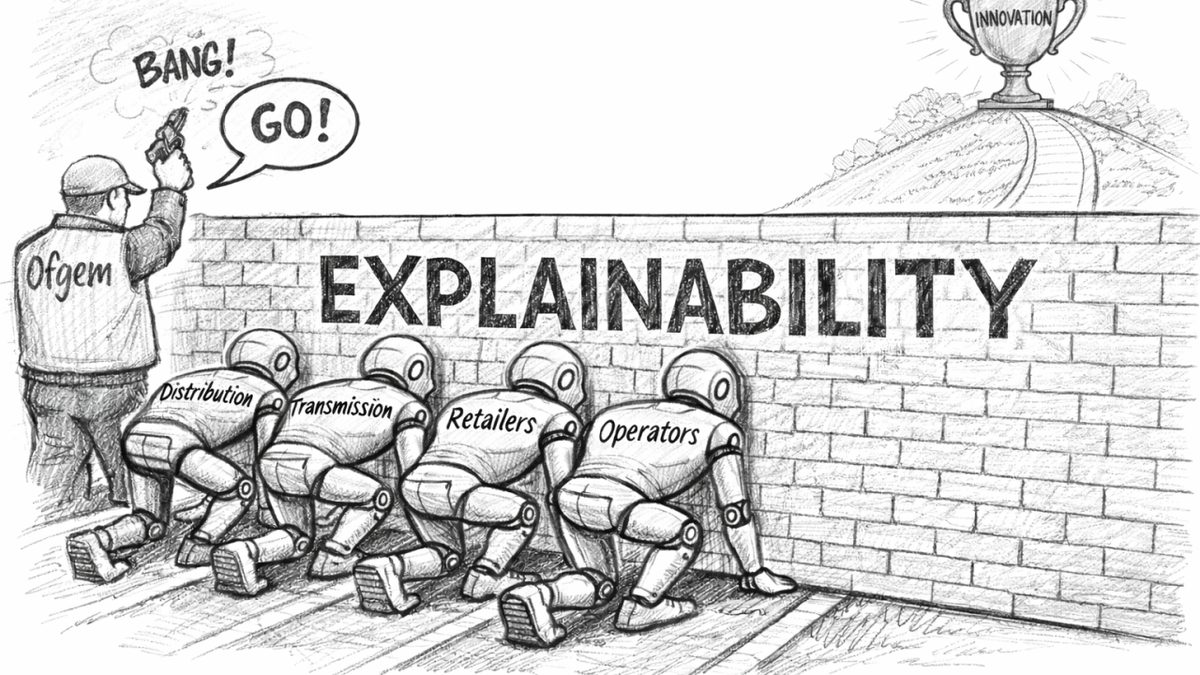

Recently, Ofgem announced it was considering strengthening the explainability and transparency aspects of the guidance. Again, the aim of ensuring that decisions made about customers are clear and fair is essential. But this objective is fundamentally in conflict with the nature of generative AI (GenAI), which is neither fully transparent nor explainable.

This is a fundamental dilemma: how can Ofgem protect customers' interests whilst enabling innovation in GenAI? Or will it inadvertently be over-prescriptive and strangle GenAI innovation in utilities before it starts?

Why GenAI Is Different

GenAI is different to traditional programming. It refers to systems that use large language models to generate content, rather than classifying or predicting from existing data. These systems are built on complex neural networks with billions of parameters that learn statistical patterns from huge volumes of training data, rather than following explicit programmed rules.

This architecture fundamentally differs from traditional AI approaches such as decision trees, expert systems, or linear regression models, which can typically be fully tested and explained. Ofgem's own guidance notes this characteristic.

The Explainability Challenge

Both transparency and explainability present distinct challenges for GenAI. Understanding why a GenAI system produced a particular output is technically constrained by the architecture itself. The UK Government's AI Playbook notes that "some AI models… can be so sophisticated that it is challenging to trace how a specific input leads to a specific output." Where implementations are built on third-party models such as ChatGPT or Claude, the training data and model architecture are essentially a black box. Full transparency about internal workings may simply not be possible.

If it's not possible to explain a GenAI solution or the basis of its design, then the only option is to focus on the controls around its implementation and management. This means examining the decision process for choosing GenAI over alternatives, the architecture that controls its behaviour (particularly guardrails that keep it aligned with correct outcomes), and the mechanisms used to monitor and ensure it remains reliable.

Alternative Approaches

Such approaches are already being proposed, even by the Government itself: DSIT's Trusted Third-Party AI Assurance Roadmap proposes using assurance mechanisms where full explainability isn't feasible. The NIST Generative AI Profile suggests organisations should "address general risks associated with lack of explainability and transparency by using ample documentation and [other] techniques." The ICO and Alan Turing Institute's guidance proposes context-appropriate explanations rather than one-size-fits-all transparency. Indeed, the ideas of using governance and risk management to oversee AI are already covered in Ofgem's existing guidance.

However, even these alternative approaches could place a heavy burden on GenAI implementations, creating overhead and administrative complexity that discourages innovation. This is where Ofgem's emphasis on context becomes key; throughout the guidance, it emphasises that governance should be proportionate to risk.

What "Proportionate" Means in Practice

But what "proportionate" means precisely is left for each company to decide. The burden of interpretation falls squarely on utilities. Even though Ofgem's publications are currently just guidance, they could become regulation, and diligent companies would want to align with the guidance whatever. So it will drive them to carefully consider where and how they should implement GenAI.

It would be reasonable to assume that any solution making decisions that directly affect customers would require the most rigorous oversight, whilst those focused on internal processes with no direct customer impact would need the least. So that's where utilities are essentially constrained to focus in the short term — on GenAI implementations in internal processes where lightweight governance can be justified. This allows organisations to learn how to implement and deliver benefits from GenAI, with reasonable confidence that their approach won't be invalidated by future regulatory change.

A Path Forward

In the meantime, Ofgem is consulting on a proposed AI technical sandbox, and this represents a valuable opportunity. By taking customer-facing use cases into that environment, the sector can explore how practical explainability and transparency could work in practice, finding a way forward that protects customers and enables effective innovation with GenAI.

This approach is not ideal, as it does mean delaying innovation for customers. Though given the maturity of the technology any company should be cautious deploying GenAI for customer-facing processes right now, and there are plenty of other processes it can be used for. However, the technology is moving fast, and the industry, if it really wants to exploit the opportunities GenAI brings, does need Ofgem to settle quickly on a solution for GenAI explainability.

References

(1) Ofgem (2025), Ethical AI use in the energy sector, OFG1164, May 2025. ofgem.gov.uk

(2) Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (2025), Artificial Intelligence Playbook for the UK Government. gov.uk

(3) Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (2025), Trusted Third-Party AI Assurance Roadmap. gov.uk

(4) National Institute of Standards and Technology (2024), Artificial Intelligence Risk Management Framework: Generative Artificial Intelligence Profile, NIST AI 600-1. doi.org

(5) Information Commissioner's Office and The Alan Turing Institute (2020), Explaining Decisions Made with AI. ico.org.uk

(6) Ofgem (2026), AI Technical Sandbox Consultation. ofgem.gov.uk